Even when I saw the synagogue burning and how they broke up our flat, I'm certain I was not afraid--really not.

Even when I saw the synagogue burning and how they broke up our flat, I'm certain I was not afraid--really not.

Joseph Heinrich was one of ten children born to a middle class Jewish family in Frankfort am Main, Germany. His father, who ran a small grocery shop, was sympathetic to the Zionist movement. By 1937, when Joseph was thirteen years old, his four older brothers and sisters had already left Germany to settle in Palestine.

Joseph Heinrich: On

November 9, 1938,

we stood by the window of our house--the house where I was born--and watched while they burned down the big synagogue across the street. The Boerneplatz Square was crowded with thousands of spectators; they made a circus out of it. We saw it all. Suddenly they burst into our rooms with axes and bars and smashed everything up.

Joseph Heinrich: On

November 9, 1938,

we stood by the window of our house--the house where I was born--and watched while they burned down the big synagogue across the street. The Boerneplatz Square was crowded with thousands of spectators; they made a circus out of it. We saw it all. Suddenly they burst into our rooms with axes and bars and smashed everything up.

We ran to the neighborhood police station for help. They looked at us and just laughed. We fled from them to find shelter with a family my father knew. Then in the evening we took a taxi to my aunt's house. That was Thursday. On Friday we saw them arresting Jewish people all day long. Friday evening, we were still with my aunt. We heard a knock on the door; they had come to arrest my uncle, my father's brother-in law.

My father said to them, "I won't let him go alone."

"Fine. You can come too," they said, and took them both away.

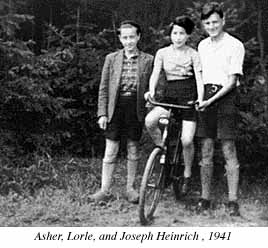

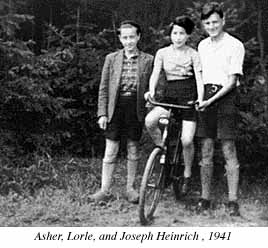

A few hours later my sister and I went to the police station asking for our father. They told us to get lost. Several days after, on the 15th of November, my mother sent my little sister Lorle, my younger brother Asher, and me to Holland. We went together with a group of about twenty-five children, organized by some Jewish women; I don't know who they were.

When we arrived at the Dutch border, two S.S. men took us off the train, into a waiting room. All the Germans had to leave the room because they couldn't have Germans and Jews in one place together--we were very dangerous people, you know; I was fourteen, Lorle was eight, Asher was twelve, and there was another child of three or four. They told us there was no toilet, no water fountain, no nothing, and don't cry. Right away the little ones started crying.

We weren't allowed to leave the room until evening when they put us aboard another train, the Reingold Express--I remember it very well. We crossed the border into Holland. When we arrived, a committee was waiting to greet us. There were journalists and photographers; everyone was asking how things were in Germany. We told them about the burning and arrests.

I don't know if I can tell you how I felt; as a young child, maybe it was like some kind of adventure; I know I wasn't afraid.

Even when I saw the synagogue burning and how they broke up our flat, I'm certain I was not afraid--really not.

Even when I saw the synagogue burning and how they broke up our flat, I'm certain I was not afraid--really not.

But when we arrived in Holland, that moment was very hard for me. I think I realized all at once that something was irreversibly broken. It was only at that moment that I understood what was going on, or maybe more, I started to think about what might be in store in the future.

The next day the people looking after us told us to write letters home letting our parents know that we had arrived safely. They made sure we stayed in contact with our families by writing every week. I found out that my father was imprisoned in Buchenwald concentration camp. But then he was set free because he managed, through a cousin, to get an afidavit for England. In 1938 Buchenwald was not yet a death camp, although there were plenty of people who never left the place. If you could show you had an affidavit to emigrate, they would set you free and let you leave the country, but it was very, very hard to do. There was practically no country in the world that would take Jews--not America, not England, none. Ships were leaving for America, but if you were Jewish you couldn't go, even if you had the money. The only place you could go to easily was Shanghai, and who had enough money to go there? --very, very few. When the Germans invaded Poland on the first of September 1939, my mother said to my father, "You must leave, otherwise they will arrest you again." But there was no affidavit for my mother. I never saw her again.

My father was on the last civilian train to cross the Holland border, and then on the last boat from Holland to England. In England he was arrested right away for being German--an enemy alien--and put in a concentration camp on the Isle of Mann with Nazis! He was there for a long time.