Joseph Heinrich: In Holland, Lorle, Asher and I were put in a home for refugee children in Den Dolder, near Bilthoven. Nearby was a school called the Children's Werkplaats. The Werkplaats was a very special place, a private school managed by Kees Boeke, somewhat along the principles of Montessori in Switzerland. Children began in kindergarten and stayed there until they were eighteen years old. Mirjam Waterman was a teacher there. Once one of the pupils told her, "Mirjam, do you know there is a group of young people--refugees--who have nothing to do? Do you think they could come to us?" It was her students who made the connection between our refugee home and their school.

Joseph Heinrich: In Holland, Lorle, Asher and I were put in a home for refugee children in Den Dolder, near Bilthoven. Nearby was a school called the Children's Werkplaats. The Werkplaats was a very special place, a private school managed by Kees Boeke, somewhat along the principles of Montessori in Switzerland. Children began in kindergarten and stayed there until they were eighteen years old. Mirjam Waterman was a teacher there. Once one of the pupils told her, "Mirjam, do you know there is a group of young people--refugees--who have nothing to do? Do you think they could come to us?" It was her students who made the connection between our refugee home and their school.

Boeke rented a special house for all of us Jewish refugees from Germany--about forty-five or fifty children. At fourteen, I was the oldest; the youngest was only four years old. Because we didn't know the Dutch language yet, they put us apart from the other children, to make it easier for them to teach us. That was how I met Mirjam: she was my Dutch language teacher.

Mirjam was very patient as a teacher; I think she felt sympathy for the little children who had to leave their families. In the beginning I think she just felt sorry for us, but later on she became really involved, with all her heart.

We became very close; if there was anything I needed to talk about, I went to Mirjam, not to any of the male teachers. There was only about five or six years difference in our ages and she was like a big sister to me.

One time she brought me home to her parents. "Mother, this is Joseph," was all she said. It was that easy. Her mother became like a mother to me--really.

My impression was that her father was a very rich man; I think he was a diamond merchant. He had some land, and orchards with apple and plum trees. He was an easygoing man. Mirjam made me a present of a bicycle; between Bilthoven and Loosdrecht, where they lived, it was only a 20-minute ride. I went to their house very often, in fact, every moment that I could.

Other children in the refugee group were friendly with them, but none were as close as I was; I was like their child; I was at home there. I could go to her mother if I felt sick. Her father had a library with a lot of books, which he took great pride in and carefully protected. No one was allowed to touch the books, but he made an exception for me.

Then in 1939, before Hitler started the war, the children at our Den Dolder refugee house were sent to live with families all over Holland. My sister Lorle went to a family in Friesland, in the north, where she stayed safely until the end of the war. Asher went to a family in Bilthoven, and I was sent to an orphanage in Utrecht.

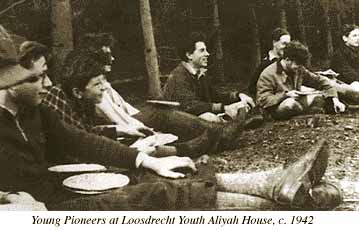

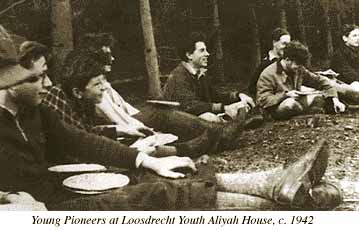

When the war in Holland broke out on May 10, 1940, the director of the orphanage sent me to a Youth Aliyah group in Zeeland. I stayed there for only two or three weeks until the Germans decided to evacuate all the Jewish people from the province. They sent me to another Youth Aliyah House, this one in Loosdrecht, in the neighborhood of Mirjam's parents. That was the connection: Mirjam knew us and our leaders who were all young people her age. Officially, she was not part of the Loosdrecht Youth House, but she came over all the time; it was only two hundred meters from her house. Now I was at home at two places: Loosdrecht and Mirjam's.

At Loosdrecht there were about fifty boys and girls my age, between fifteen and seventeen. On a certain day we got an order that we had to go to Westerbork concentration camp, the whole group together. The leaders decided to hide us instead, although they had only a few days to make the arrangements.

The Westerweel Group: Mirjam was the link between our Loosdrecht leaders and several teachers from the Werkplaats school in Bilthoven. They formed a group headed by Joop Westerweel, a non-Jew. I was in his home quite often before all the troubles began. He was a really special person, a very strong man. For Joop there were only two sides: something was either right or it was wrong.

He said, "It's wrong to persecute people for their religion or race. It's wrong, and you must fight wrong without compromise."

The Dutch government had prepared identity cards for everyone in Holland before the war even started; there was nothing like it in any other western European country, not even in Germany. So when the Germans came in, they found the whole Dutch population registered and accounted for. That made it easy for them to find people, and difficult and dangerous for underground work.

Joop had refused to take an identity card for himself or his family. "I'm not a sheep to be herded," he said, "I'm a human being." But when he began to work in the underground he took an identity card--a false one, of course. He and his wife, Willie, went into the war without any compromise, even though they had four children, and Willie was pregnant. A Christian person risked everything by helping Jews--his whole family. When Joop and Willie were caught they had to hide their children, including a baby who was less than a year old.

Joop left his teaching job, and Mirjam became one hundred percent involved after we went into hiding. It was not the kind of work you could do part time. They had to go around to all the places where we were hiding and bring money, false identity papers, and ration stamps to the families looking after us. They also had to travel all over Holland, constantly looking for new families that would take us in. It's a small country, but in those days travel was not so easy. Even if you had a car, there was no gasoline. There were curfews, raids all the time, and German guards at every station checking identity papers on the trains. It was a full-time job.