Joseph Heinrich Tells His Story (continued)

Joseph Underground: The first underground place I was sent to was the home of a painter in Arnhem. I was in a group of eight or nine boys there; the time had been too short to find a place for each of us. This artist had a Jewish girlfriend who was caught by the Germans after we had been with him for only two or three days.

We had to leave quickly, in case they decided to search his place. Within a few hours we were taken to another address in Arnhem. A few days later, my brother and I, and a young Dutch student, not a Jew, moved again, to a place near Appeldorn. This man's name was Urban, and he was known far and wide as a communist.

Whenever something bad happened in the neighborhood, they called on Urban first.

Whenever something bad happened in the neighborhood, they called on Urban first.

One night the Dutch police came again to arrest Urban for something or other. We were sound asleep and didn't hear them coming. Suddenly I heard a policeman asking me, "Where's your identity card?"

"I'm only fourteen years old. I don't need an identity card."

"You are only fourteen?"

"Yes."

"Get dressed then. You have to get out of here."

It was two o'clock in the morning. My brother and I and this Dutch boy, who had false papers, left the house, out into the cold and rain. We went to the neighbors to ask for shelter, but nobody would open their door. They didn't know who we were, but they knew we had been staying with Urban--we had his stigma.

All night long we stood in the rain, waiting for daylight. Then, soaked through, we took a bus to Amsterdam and made a connection with some members of our Westerweel group; they found another place for us. That's how it went: you had to change places all the time.

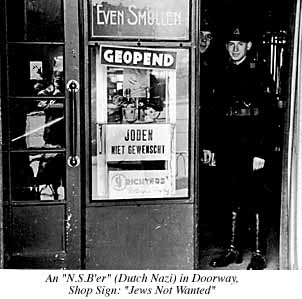

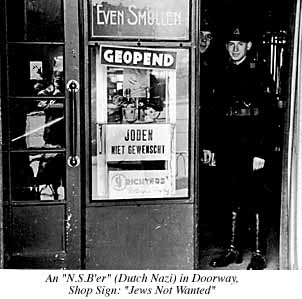

So many things happened, you couldn't stop to think too much about any of it. You just knew you had to go from point A to point B, and that's all. You could go straight, or go around; you had to figure it out for yourself. Nobody told you how to behave--only the newcomers didn't know. One thing you learned was that when you see a German, don't step off the pavement, but walk straight ahead; it's your right to walk on the sidewalk.

Don't act afraid, or cross the street, or they'll look at you. Don't look over your shoulder. Behave like other people. Coming from Germany, our language was German, of course, but if a German speaks to you in German, don't answer. Sometimes they would be standing right behind you and say, "Come here!" You couldn't turn your head. We spoke in Dutch and the Germans couldn't detect whether or not it was with a German accent.

I didn't see Mirjam again until after the war, but Menachem, our Loosdrecht leader who became Mirjam's husband, I saw very often. I was also in frequent contact with Jan Smith, a teacher from the Bilthoven Werkplaats, and he saw Mirjam frequently. He brought me her greetings and news; I always knew what was going on with her and her family. I knew when they went into hiding, but I didn't know where. No one wanted to know more than was necessary.

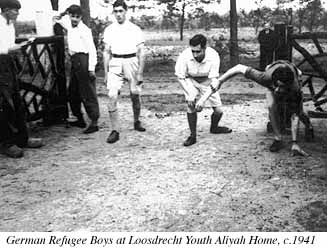

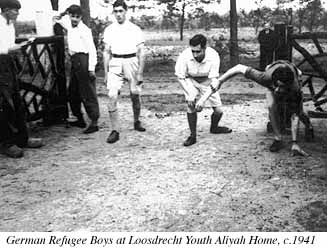

Menachem was an intellectual. He worked at the Youth Aliyah house as a teacher and a leader, but by profession he was an engineer. A man named Lodi Cohen was the head of the Loosdrecht leaders, and Menachem was second. There were four altogether--Cohen, Menachem, Hanna Asher and Adina Simon, who was married to Shushu.

It was not easy for these leaders to work with us. We were children who had left our families, there was the war, and on top of that there were all these German decrees on how we were to behave, such as Jews having to wear the star--I think I wore it only twice. We were a group of youngsters--fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old--and our leaders were only twenty-two, or twenty-four years old themselves, yet they were completely responsible for us. They worked very hard.

It was not easy for these leaders to work with us. We were children who had left our families, there was the war, and on top of that there were all these German decrees on how we were to behave, such as Jews having to wear the star--I think I wore it only twice. We were a group of youngsters--fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old--and our leaders were only twenty-two, or twenty-four years old themselves, yet they were completely responsible for us. They worked very hard.

I don't think I was an especially good boy. One time my brother and I and another boy, Dov Ascheim, decided to run away from Loosdrecht to be on our own. We made a connection with the secretary of the village to provide us identity cards without the incriminating "J" (for Jew) stamp. But then he went to our leaders telling them that three of their boys might be planning something. Menachem took me aside and said, "Joseph, we will all go into hiding together. Give me your identity card, and don't make trouble." It was a very hard responsibility for a young man like him to take on; he couldn't know whether he would succeed in hiding us.

Every one of them could have saved themselves. But if all the leaders went away, who would take care of the children in hiding? Somebody had to stay in Holland to go on working. The shepherd cannot leave the flock. I think they had to be very very brave and courageous to take on this task. What they did was a very great deed. And they paid the price.

Shushu, for example, brought his wife to Switzerland and he was

caught

on the way back. Afraid that he would say too much, he asked for a razor blade from the policeman in the prison, and committed suicide.

It was not easy for these leaders to work with us. We were children who had left our families, there was the war, and on top of that there were all these German decrees on how we were to behave, such as Jews having to wear the star--I think I wore it only twice. We were a group of youngsters--fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old--and our leaders were only twenty-two, or twenty-four years old themselves, yet they were completely responsible for us. They worked very hard.

It was not easy for these leaders to work with us. We were children who had left our families, there was the war, and on top of that there were all these German decrees on how we were to behave, such as Jews having to wear the star--I think I wore it only twice. We were a group of youngsters--fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old--and our leaders were only twenty-two, or twenty-four years old themselves, yet they were completely responsible for us. They worked very hard.

Whenever something bad happened in the neighborhood, they called on Urban first.

Whenever something bad happened in the neighborhood, they called on Urban first.